- Home

- Walt Williams

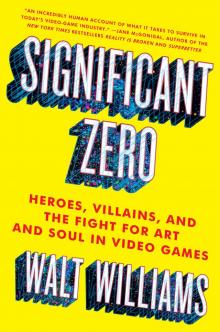

Significant Zero Page 7

Significant Zero Read online

Page 7

That brings us to the second item on my must-haves list: a gym. If I was going to be stuck in one place for a while, it seemed a good idea to spend time on self-improvement. Clearly, my dietary habits were not the best: a lot of carbs, fat, and cholesterol with the occasional vending-machine dim sum sprinkled throughout. Hitting the treadmill three or four times a week not only helped to keep off the weight, it also helped battle depression. Hotels are lonely places, devoid of the personal baubles and trappings that triggered my sense of comfort. The longer I stayed in one, the more disconnected I felt from myself. This was only exacerbated by the alcohol I guzzled on a nightly basis. Remember, alcohol is a depressant. The sadness it brings will sneak up on you. For me, regular exercise fought it off, but only for so long. Eventually, I would have to resort to the third item on my list.

If you’re going to live in a hotel, you have to bring your own entertainment. This is easy to accomplish these days, but iPhones and iPads weren’t a thing back in 2006. My only options were analog—books, comics, DVDs. If the TV in my hotel room had the proper hookups, I’d even bring along my PlayStation 2. I always packed too much. Better to have too many options than none at all. Working my way through a book or show gave me some sense of accomplishment, enough to convince me the hotel wasn’t syphoning off what limited time I had left on this earth. Eventually, I streamlined my entertainment to focus only on complete runs of classic TV shows. I didn’t care what the show was about, so long as every season was available on DVD. Reading and games were fun, but I needed something that required a minimal amount of focus. I often got insomnia when I traveled, and it absolutely wrecked my cognitive abilities. If I hadn’t slept in forty-eight hours, the written word took on an incomprehensible, alien swirl. All I could do was lie in bed like a coma patient, absorbing stimuli by osmosis, never fully awake or asleep—whatever it took to ensure I wasn’t alone through those long nights. Being alone only led to questions, the kinds you never want to ask.

Terrible, right? Wrong. Working on-site was fantastic, and I’ll tell you why.

Money.

You may not have heard, but New York City is expensive. While my job came with all the perks and benefits, it was still an entry-level position. I was paid a reasonable salary for my role and experience. Reasonable won’t always cut it, though.

When working on-site at the studio, my daily cost of living was covered by the company. Food, shelter, and transportation could all be expensed—basically free money. If I’d been working in the New York office, I would have paid for food and transportation out of pocket. When you’re young and just starting out, extra cash is very enticing. It’s great for paying off loans or building up a savings account. You just have to be able to resist its siren call.

“I’m thinking of giving up my apartment,” said D. T. We were catching up over lunch. Both of us had been on the road for a while, and this was a rare opportunity to sit down and talk. “I’m never in town. When I am, I usually just crash at my girlfriend’s place. Might as well save some money.”

“Is she going to be cool with you moving in?”

“Cohabitation? Walter, what are you thinking?! This is freedom we’re talking about: no apartment, no rent, nothing. Imagine how much money you’d have if you weren’t paying rent every month. Just living in hotels, expensing all your meals like a professional hobo.”

We hadn’t been around long enough to realize money could only get you so far. There’s actually an emotional arc that occurs when your earnings suddenly increase. You start by convincing yourself to work harder, as if you need to prove you’re worth it. As the stress rises, your mentality shifts, and you accept that you are being adequately compensated for what you’re doing. The more you prove yourself, the more people begin to rely on you alone. You’ve always been able to handle things in the past, no matter what it took; there’s no reason for that to change. It’s then that the truth finally hits you—you’re not paid nearly enough to deal with this shit.

Money is necessary to our physical survival. That’s just capitalism. To keep our spirit alive, we also need a sense of purpose. How you find that depends on the type of person you are. Maybe you’re working on your dream project, or you want to show the world what you’re capable of, or perhaps you’re just the kind of broken, malformed mutant for whom the work itself is enough. Whatever does it for you, heed my advice—find it fast, then suck every last drop of marrow from its bones. Without its nourishment, you will not be long for this world.

For me, that purpose was writing. Eventually, HVS would get around to writing the script for the Family Guy game. I knew if I hung on long enough, I’d get to be part of it. Then, I’d show 2K, the Fox, and everyone else just what I was capable of.

When the time came, it was decided to bring in the Family Guy staff writers; that way the game would match the quality and humor of the show, plus it would be a great selling point. I was instantly opposed to the idea. I wanted to write the game, or at least part of it. If the show writers got involved, they wouldn’t need my talents. Luckily, the Family Guy staff didn’t have time to write the script; they were too busy making a TV show. We floated the idea of HVS writing the first draft and then sending it to the show writers for a final polish. They agreed. This was my chance. All I had to do was find a way to insert myself into High Voltage’s writing process.

If you’ve ever wondered why so many games have bad writing, it’s because developers don’t usually have a dedicated writer. It’s more common now, but a few years ago, it wasn’t out of the ordinary for a script to be cobbled together by anyone who cared enough to force their way into the discussion. It was a train wreck of designers, coders, and artists pushing for their ideas. This sort of thing doesn’t happen in other disciplines. Art and design occasionally, but take programming, for instance. Try telling programmers you want to do a studio-wide review of their code and see which breaks first—the game or your legs. I don’t know why, but when it comes to story, suddenly everyone’s a writer. The script you end up with won’t necessarily be bad; oftentimes it’s perfectly passable. But there’s a wide margin between good enough and great, and the quality jump is always noticeable.

The script HVS sent us was, in my opinion, rough. I freely admit I was biased; after all, I didn’t write it. On top of that, it just didn’t read like Family Guy to me. I told the Fox we couldn’t send it to the show writers; they’d have to start over from scratch. As far as I could see, the only way forward was for me to rewrite the entire script. All I needed was five days.

In college, I had a process for writing a lot in a short amount of time. I’d isolate myself, usually by dragging a desk into a storage closet. Then I’d write by hand, using different-colored pens to help me keep track of sections and corrections. Once I’d written fifty pages, I’d type them up, print them out, and sleep for six hours. When I got up, I’d slash and burn the printed pages until I was left with ten to fifteen pages of usable material. Then I’d pick up where those pages left off and do it all over again. I did this Monday through Friday, every week. It was an effective process, and even though I’d have to modify it for working in the office, I knew I could use it to finish this script within five days.

The Fox didn’t buy it. “I’ve never worked with a writer who could write a script in just five days.”

“To be fair, none of those other writers were me.” Cocky, I know. I had to be, because I had nothing to back it up.

Being an artist isn’t like being an accountant or a doctor. People need medical care. If you can provide it, you will never want for patients. People also need art. It speaks to who we are as individuals, as well as a species. That doesn’t mean they need your art.

Anyone with a proven track record can be confident. When you’re just starting out, you have to convince yourself that you are talented and worthy of recognition; otherwise, you’ll be held back by self-doubt. In other words, fake it until you make it.

My arrogance and narcissism must hav

e resonated with his French blood, because he gave me the go-ahead. Hidden away beneath a stairwell, I spent the next week rewriting the game’s script. In my opinion, the resulting product was pretty good. Even the Fox agreed. We fired it off to the developer and went home for the weekend.

Come Monday morning, there was an email from HVS’s producer waiting in our inboxes. To my surprise, he wasn’t angry; he was disappointed. His team had worked hard on the script, and he couldn’t understand why it had been rewritten. “This isn’t a rewrite. It’s an entirely new script. The whole thing is just an excuse for Walt to replace our stuff with his.” All valid points, but it didn’t matter. This was the plan the Fox and I had agreed upon. HVS’s script never would have passed muster had we sent it to the show writers. We were on a tight schedule, and there was no time to make sure everyone’s delicate egos remained unscuffed.

A week or so later, we flew from New York City to Los Angeles to meet with the show writers and discuss the script. I was over the moon. I’d written a full game script—based on the hit TV show Family Guy. That script had been read by the show’s actual writers. Just a few months ago, I was unemployed with no career prospects. Now, I was flying to Los Angeles to visit the FG offices and meet with the people who made the show. This was my moment. Anything was possible.

“The script is bad. Like, really bad. One of the worst things I ever read.”

It turns out anything was possible, including having my script ripped to shreds. So much for my dreams of collaboration. I tried to hide my disappointment, but my poker face is weak. I think the show writers could see they were tearing my heart out, because they toned down the criticism. No concessions were given, not even a “Nice try” or “It wasn’t all bad.” But they stopped calling it the worst thing ever, instead choosing to focus on how much work it would take for them to fix it.

The Fox and I left the studio completely dejected. We thought we’d brought our A game, but Hollywood shut us down real fast. We were just a video-game publisher. The “real” writers would take it from here. I’d been shut down in the exact same way I’d shut down HVS. Had I been wiser at the time, I might even have learned a lesson from it all: It doesn’t matter how good you think you are. It doesn’t even matter if you’re right. All that matters is the opinion of the next person down the line.

* * *

MONTHS PASSED, AND WE finally got the final script from the show writers. The story was basically the same, but the words and jokes were different. That is, every joke except for one.

It was at the end of a scene in which Carter Pewterschmidt and the police show up at the Griffin house, looking to arrest Brian for once again knocking up Carter’s prized dog, Seabreeze. Brian denies the allegations, but Carter won’t hear it.

Carter pulls a stack of cash out of his pocket and hands it to the Cop.

CARTER

He’s lying.

Carter hands the Cop a second stack of cash.

CARTER

And he’s not Caucasian.

The Cop runs into the room and beats Brian with his nightstick.

“Good for you,” said the Fox. “I’ll make sure you get an additional credit on the game.” And he did. When the game shipped, I was credited under Additional Writing and Design, which is a nice way of saying I put words and ideas in the game, though not in any official, titled capacity.

The Fox dropped what looked like a tube of toothpaste onto my desk. “Here. I got you something.” He’d been traveling overseas the previous week. He must have bought souvenirs.

The tube had a picture of a reindeer on it. “What is it?”

“Consider it a bonus for all your hard work.”

I uncapped it and squeezed some onto my finger. It looked disconcerting: a grayish-white paste with bits of darker gray things scattered throughout. Was it some weird, foreign Christmas treat? No. It was pureed reindeer. And it had already gone bad.

As I stood gagging in the office kitchen, trying not to vomit in the sink, I couldn’t help but feel like I’d won somehow. One joke wasn’t much, but my foot was now in the door. From there, I could move on to writing generic lines, a whole character, maybe even a script for an entire mission—more and more, until every word was mine.

6

* * *

ENRAPTURED

In 2006, Take-Two Interactive announced it had acquired acclaimed developer Irrational Games. Founded by Ken Levine, Jon Chey, and Robert Fermier, the company had made its name developing the PC games System Shock 2, Freedom Force, and SWAT 4. All three were former employees of the legendary Looking Glass Studios, which gave the world the beloved System Shock, Ultima Underworld, and Thief franchises.

You might be curious why a developer of such caliber would choose to sell itself to a publisher. I wish I could tell you; unfortunately, I don’t have any special insight. Every acquisition is different. That said, if I owned my own development studio, I can tell you why I would want to be acquired.

Developing games is hard. As an independent developer, even a successful one, you’re reliant on contracts and other companies for publishing, marketing, distribution, and more. It’s exhausting, and can feel like you’re always on the verge of collapse. There’s stability in being acquired. You’ll always have projects to work on and enough cash flow to cover payroll. It removes some of the pressures of being a salesperson for your company and its games, as the publisher now becomes your advocate. More importantly, you gain access to their marketing, distribution, and sales force, which in theory should lead to more success for everyone involved. There are trade-offs, of course. You might give up some creative control, along with any intellectual property and franchises you might own, but that’s not necessarily a given. Like I said, every acquisition is different. It all comes down to the contract.

Once acquired, Irrational’s latest project, BioShock, became part of 2K’s lineup. The game was a story-driven first-person shooter (FPS) set in Rapture, a city of scientific wonder founded on Objectivist ideals by industrialist character Andrew Ryan. For a video game, that wasn’t nearly enough of a hook. Rapture wasn’t just a fantastical city; it was also an impossible one, having been built at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean in the late 1940s. And while it would have been fun to shoot your way through a city of cultural elites who ran away to live in a private ocean paradise, it wouldn’t have been much of a challenge. Luckily, those upper-class hoity-toities had been transformed into superpowered drug addicts who killed little girls to feed their need for ADAM, an addictive, gene-altering wonder goo.

BioShock merged the intellectual elitism of Ayn Rand with the low-class entertainment of beating things to death with a wrench. It walked the line between serious and absurd, and in doing so embodied exactly what I love about video games. I couldn’t wait to work on it.

BioShock was planned as a spiritual successor to Irrational’s first and most celebrated game, System Shock 2. Set aboard a spaceship in the year 2114, System Shock 2 is a first-person shooter/survival game about a soldier who teams up with an evil computer named SHODAN to destroy the Many, an alien hive mind that threatens to consume every living thing it encounters. System Shock 2 is a celebrated game for many reasons, first and foremost being the game’s terrifying villain. It’s also beloved for its unforgiving level of difficulty. Your in-game character is physically weak, while the enemies you encounter can often kill you in just a few hits. Your weapons degrade every time you use them, until they become worthless. Even if you manage to kill all the enemies in a given area, you’re not safe; they can respawn anywhere, anytime.

To play System Shock 2 is to understand that you are a fragile, mortal being whose life could end at any moment. I’ve never played System Shock 2—and probably never will—and this is the reason why. As I see it, life is hard enough. I don’t need to be tortured in my free time. I’m sure System Shock 2 is a fantastic game, it’s just for a different type of gamer. I want the games I play to be fun; other people want games that hate them

on a primal level.

With BioShock, Irrational promised to bring the dark narrative and immersive gameplay of System Shock 2 into the modern console era. This terrified the Fox. Games had changed a lot since 1999. Console games were far less difficult than the PC games of old. The Fox knew BioShock would be phenomenal, but he was afraid it would be too punishing for a mainstream audience. He wanted to keep an eye on the game, just to make sure it didn’t become insanely difficult.

“We’re going to Boston next week to meet with the team,” said the Fox. “You’re invited to come, but on one condition.” Anything. “I need you to not do that thing you do during meetings.” Thing? What thing? “You know, the look you give to whoever is speaking. The one that says, ‘You are the dumbest person I’ve ever met.’ ”

“Do I give you this look?” I asked.

“All the time.”

Oh, shit. “. . . Am I giving it to you right now?”

“No. Right now, you look scared.”

Of course I was scared. I’d just learned my face was constantly telling my boss to fuck off. “So, here’s the thing about my face—”

The Fox waved off my explanation. “It’s fine; I’m used to it. Just don’t do it to Ken.”

I wasn’t going to be part of the difficulty discussion. The only reason I tagged along was so I could meet the team and discuss the creation of promotional assets, aka screenshots.

When you think about screenshots, you probably think of fakery: pictures of a game, purported to accurately convey its look and feel, taken from impossibly dramatic angles, touched up using Photoshop—all to make you think a game looks better than it actually does. They call this a bullshot. It’s an appropriate term, but if we’re being honest, even an accurate screenshot is a lie.

Significant Zero

Significant Zero