- Home

- Walt Williams

Significant Zero Page 10

Significant Zero Read online

Page 10

* * *

I’VE NEVER WORKED ON a game I didn’t hate.

As the saying goes, familiarity breeds contempt, and there is no greater intimacy than that obtained through creation. By the time BioShock was released, I’d played the game more than two hundred times. My cursor had caressed every hair, blemish, and wart on its digital frame. I’d seen everything, except the final game 2K had shipped to stores across the world. BioShock had gone gold without me. I had no idea what changes had been made in the final stages of development. I didn’t want to know. When the Fox gave me my retail copy of the game, I tucked it away in a drawer. There was no way I could play it. The memory of working on BioShock was still too fresh.

A person is just an animal with a very high opinion of itself. We don’t like to think about it too much, but we’re as trainable as dogs. If an action is continuously repeated, our mind will build connections between the action and associated stimuli. Video games demand everything of their creators. With BioShock, I wasn’t even involved with its creation; I was just the guy taking pictures, and it still wrecked me. Three months passed before I found the energy to play it.

On a Saturday morning, I placed the game in the disc tray of my Xbox 360. The game spun up; the 2K and Irrational Games logos appeared and then faded from my TV screen. When the start menu appeared, I did nothing. It was night. Moonlight streaked the cloud-covered sky. The game’s logo—an iron-cast plate bearing its name and an abstraction of a city skyline—floated above the Atlantic Ocean, at the base of a lighthouse. The water rippled gently; the rays of moonlight moved in time with the clouds. It was the first time I’d seen the final menu, and it was beautiful. When I saw that, I knew I was finally ready.

I selected “New Game” and descended back into Rapture. Minutes later, as my bathysphere surfaced inside Rapture’s welcome terminal, the game froze. At first, I thought the game had simply crashed. Even with high-profile releases like BioShock, it wasn’t out of the question for a game to ship with bugs still inside. Then I noticed the power button of my Xbox 360. Normally green, it was now surrounded by three flashing red lights. My console had suffered a general hardware failure that the gaming community had dubbed the Red Ring of Death. I was ready to play BioShock, but my 360 clearly wasn’t. It had fatally shat itself and was now an expensive brick, broken beyond repair.

For the first time in a long while, I went outside and enjoyed the day.

7

* * *

MADE MEN

A few years into the job, life took a turn.

I was in a long-term relationship. It ended. The details aren’t relevant to what we’re talking about, except for one—I was more willing to commit to my job than to my personal life. Coming out of college, I had no career prospects. Now, I was working for a major video-game publisher, traveling the world, and standing near brilliant people creating spectacular things. It was easy to be seduced.

She wanted to move back south. I said no. This job was for me; New York City was for me. It hurt, but I needed to stay.

The day after she left for good, I was on a plane to Berlin. Work didn’t stop for doubt, regret, or heartbreak. That night, the Fox grinned at me from across a table in the bar of our hotel.

“So . . . What do you think of San Francisco?”

The mischievous twinkle in his eye said everything his question had not.

“I think you’re an asshole.”

2K was growing and needed more room. The plan was to trade our single-floor office in SoHo for a converted airplane hangar in Novato, California, a small town thirty miles north of San Francisco. Publishing wouldn’t be alone; we’d be sharing it with 2K Sports; their main developer, Visual Concepts; and our newest internal dev studio, 2K Marin.

The Fox didn’t expect me to blindly follow him to the other side of the country. An offer was made—a generous one, which included a promotion from game analyst to associate producer. It was tempting, but I was in no rush to accept. I was one day removed from my last major life change, and was suddenly facing another. If I went to California, I’d be leaving the first city that had ever felt like home to me. On the other hand, if I didn’t accept the Fox’s offer, I’d be out of work. Staying in New York meant finding a new job, and there weren’t many video-game options in New York. It was possible I could have transferred to Rockstar, but I had no desire to. There was nothing wrong with them; their games just weren’t my style. The open-world design of Grand Theft Auto was interesting, but the series’s core crime fantasy didn’t appeal to me. Most likely, I’d have to abandon video games entirely and find employment in a new field. The third option was to leave New York and 2K, move back south, and attempt reconciliation.

A month before, I had had a fiancée, a career, and a great life in New York. I should have known it was too good to be true. Something had slipped by in the paperwork, and the cosmos had finally noticed the error. The choice ahead of me was the universe’s way of saying sorry. I was only supposed to get one of the three.

* * *

IT HAD BEEN AWHILE since I tried the comic-book thing, so I updated my résumé and sent it off to Marvel and DC Comics. Would you believe it? For the first time ever, I got a response.

With Marvel, I got a few rounds into the hiring process for an assistant editor position. Through an accidental slip in conversation, I learned I wasn’t the only person at 2K vying for the job. A few of us had secretly applied, all for the same reason—we didn’t want to move. Marvel was our Hail Mary, but none of us managed to pull it off. I don’t know how it went down for everyone else, but I can pinpoint exactly where I went wrong.

As a test, Marvel had me edit a few comic scripts. The first one was fine; I corrected typos, called out inconsistencies, kept it simple. Making it to the next round must have gone to my head, because the second script was less an edit than a full rewrite. It was a bad habit, one the Fox encouraged but no other company would tolerate. Rewriting the Marvel script was a bad decision, made even worse by the fact it had been written by Chris Claremont, the most prolific X-Men writer in comic history. Two of the six X-Men movies are based on his classic stories “The Dark Phoenix Saga” and “Days of Future Past.” Claremont is the guy who transformed Wolverine from a vertically challenged Canadian nobody into one of the most popular comic-book characters ever created, arguably making him the godfather of Hugh Jackman’s entire acting career.

I never heard back from Marvel after that. I’m still holding out hope for the mail-room job, but only because I’ve now mentioned it three times. Like Beetlejuice or Candyman, an email from Marvel’s hiring department should appear in my inbox any day now, just to say, “We have received your application and regret to inform you . . .”

DC Comics was a different story. I was browsing through a comic-book store one afternoon when I got a call. Someone at DC had seen my résumé and was so excited that they wanted to cut straight to the chase. My credentials were perfect for the position, but they were afraid I would want too much money. I’d been working an entry-level position while living in New York; too much money was not a concept I was familiar with. All I knew was what I needed to get by, month to month. DC came in five grand lower and couldn’t budge, so that was the end of it. I had missed my window of opportunity: after years spent applying with no response, I was now overqualified.

There were no other jobs in New York that excited me at the time, so my options were down to two: go west or go home.

In the end, it all came down to Berlin. Up to that point in my career, every game I worked on had been someone else’s project, a work I had joined in progress. The game being made in Berlin was different. I’d been involved with it since the beginning, and in that way, it was mine. Even though it was still in the early stages, I knew it had the potential to be unique. If I stuck with 2K, I could help guide it. I’d finally have an original AAA game on my résumé, one that showed what I was capable of. Once I had that, I could go anywhere—maybe even find work down south.

When I looked at it from that angle, it really was the only option.

We were still in the final days of shipping BioShock, so there wasn’t time for me to visit the Bay Area and find an apartment. The best I could manage was a place near the new office that would allow me to sign a lease from New York. Once that was done and BioShock had shipped, I loaded my stuff onto a moving truck and then flew to Prague to meet with a developer. Work wasn’t going to stop for something as trivial as moving across the country. One week later, I flew from the Czech Republic straight to San Francisco, where my new life was waiting.

* * *

CALIFORNIA WAS BRIGHT.

Where I lived, in San Rafael, there were trees and mountains and one road. The 101 was the Mississippi River of highways. All roads were tributaries, leading me back to that black stretch of asphalt.

They said the weather was perfect, though based on what scale I can’t even imagine. It would rain for a few months and then burn for a few months. The rest of the time, it was simultaneously hot enough to make you sweat and cold enough to require a jacket.

The closest food was always fast food, but I won’t count that as a negative.

More than anything, though, it was bright. I don’t know if it was the lack of clouds or ozone, but it always felt like there was too much sun. My body is made of marshmallow; pale and lumpy but delicious. The prospect of a sun-kissed life did not appeal to me the way it did to my friends. By the time I arrived, they had all taken up hobbies, like hiking, softball, or windsurfing. California had shown them our industry’s version of the Holy Grail—the elusive work-life balance. They had been transformed into healthier, happier, tanner versions of themselves.

Not much had changed for me. I’d roll into the office around 10:00 a.m. and roll out after sundown. My Red Bull habit, once one can a day, had grown to four before lunch. Every so often, someone would stop at my desk and look down at me with a white-toothed smile and say, “We’re going to get something to eat. Wanna come?”

“Fools!” I’d shout. “Blind fools! You’re all living a lie!”

Our job required regular human sacrifice; blood was needed for the gears to run smoothly inside the gaming mill. My coworkers believed their lives had improved, but I knew there would be weeping and gnashing of teeth when our dark digital gods grew hungry once again. Only I would be deemed worthy, for I had stayed the course and never abandoned my righteous misery for the false promises of surf and sun.

I didn’t get invited out a lot in those days.

Said a coworker, “It’s nice to know if anyone ever asks what type of person Walt Williams is, I can say, ‘He’s the type of person who gets angry when you invite him to lunch.’ ” I know I shouldn’t be proud of that, but goddammit, I honestly am.

* * *

WITH MY PROMOTION TO associate producer, 2K was left without a game analyst. BioShock had shipped, but BioShock 2 was already gearing up, plus Mafia II and Borderlands were just around the corner. “We need Walt 2.0,” said the Fox. “Who do you know?”

There was a guy—Young Philippe, a friend from my college days. He loved video games more than anyone else I’d ever met, and there was a period of time when we had the same haircut and people thought we were brothers. These are not the best criteria for hiring someone, but when the Fox said he needed Walt 2.0, this is what popped into my head.

I called Young Philippe to see if he’d be interested. “So, how are things?” I asked.

Things were good for Young Philippe. He was about to graduate from college, his final exams were done, and he was free as tap water for the next two weeks.

“I’m loving life, and it is loving me right back,” he said.

This type of unfettered positivity usually made me nauseous. Coming from Young Philippe, it was contagious. His excitement and hope were rooted in childlike wonder. At some point in life, he simply decided to not grow old and bitter. This was enough to recommend him for the game analyst position. New blood is important in the game industry; there’s nothing more uplifting to a team of bitter developers than bright-eyed enthusiasm.

I explained the situation—we were looking to hire a new game analyst, and he was perfect for the job. If he was interested, I’d see about getting him an interview.

“For real? Oh, man. I really appreciate that, but honestly, I already have plans. After graduation, I’m moving to Austin to become a rock star and an astronaut, so I’m pretty well set. But thanks for thinking of me!”

There was such conviction in his voice; I didn’t have the heart to tell him it was ridiculous. The conversation was over. I had offered Young Philippe his dream job, and he passed so he could become Ziggy Stardust. Nothing beats Ziggy Stardust.

Two weeks later, I woke up to a text message at 5:00 a.m. on a Sunday morning. It was Young Philippe. “Hey, man. Were you serious about that video-game job? Because I graduated yesterday and it just hit me I don’t have any job skills.”

Of course I was serious. “Send me your résumé. I’ll see what I can do.”

I’ve always been aware of how lucky I was to find a job at 2K when I was just starting out. I owed a lot to Wayne, the hiring manager who’d been willing to give me a chance. I’d always planned to pay that kindness forward. Young Philippe just so happened to be the guy to pay it to.

The Fox took some convincing. He didn’t see the point in interviewing someone in Waco, Texas, when there were plenty of great candidates in the Bay Area. Even if Young Philippe got the job, 2K would never pay to relocate him for an entry-level position. I told him relocation wouldn’t be an issue. To sweeten the pot, I even promised that if 2K flew Philippe out for an interview and chose not to hire him, I would personally pay back all travel costs. That did it. We set a date and prepared for Young Philippe’s arrival.

“Should I wear a suit?” he asked.

“Absolutely not,” I said. “Don’t even pack one.”

“Everyone says you’re supposed to wear a suit to a job interview.”

“Everyone is a liar. You are to wear jeans, tennis shoes, an untucked dress shirt, and your GWAR belt buckle.”

Silence on the other end of the line. Then, “I don’t think that accessory is appropriate.” Were this any other job, Young Philippe would be correct. GWAR is a hard-core heavy-metal band known for their grotesque costumes and concerts filled with over-the-top violence and gore.

“Trust me. Wear the damn belt buckle.”

* * *

WHEN YOUNG PHILIPPE SHOWED up for his interview, he wowed everyone in product development. He was smart, inquisitive, and driven. The kid knew this was his only shot at working in video games, and it pumped him full of adrenaline, keeping him at the top of his game.

The Fox was Young Philippe’s last interview of the day. Before going in to meet Philippe, he stopped by my desk.

“So, is there anything I should know before I speak to your friend?”

An idea popped into my head, sudden and mischievous. “He majored in French.”

The Fox’s eyes lit up. French, after all, was his native language. “Oh! This will be fun.”

I watched the Fox enter the glass-walled conference room where Young Philippe was seated. The door closed. The Fox sat down, put his feet up on the conference table. His lips began to move. Young Philippe’s body instantly tensed; he sat up straighter in his chair. I knew the Fox would have launched right into speaking French, and I smiled to myself.

It couldn’t have been more than ten minutes later when the Fox exited the conference room.

“How’d it go?” I asked.

He tossed Young Philippe’s résumé on my desk like it was garbage. “His French is terrible.”

Oh, no. Had my joke just cost Philippe the job? “I’m sure he’s just rusty. Aside from that, what did you think?”

Never one to give an easy compliment, the Fox shrugged. “Eh. He’s a good kid. I think he’d fit in well, but . . .” His voice trailed off, and his brow scrunched down in thought. “Wa

s he wearing a GWAR belt buckle?”

“Yeah.”

“Then why the fuck haven’t we hired him yet?”

* * *

YOUNG PHILIPPE MOVED TO California a few weeks later, with nothing but a suitcase full of clothes. He wouldn’t last long in San Francisco on his own, so he moved into my apartment in San Rafael, where he lived on my couch. I knew it was a mistake almost instantly.

At work, Philippe was amazing. Our desks sat next to each other. Against the wall, behind us, we began building what we called the Death Shrine, a pile of empty cigarette packs and Red Bull cans. Every day, we added one pack and four cans. To us, it was a sign of how hard we were working. To everyone else, it was a trash heap. Like me, Young Philippe was aware of how lucky he was to work at 2K. It felt like at any moment the shoe would drop and someone would realize he didn’t belong. Philippe’s fear of being fired and returning home a failure kept him at the top of his game. At home, however, he was just so damn happy.

My day-to-day life in California was simple. I woke up around 8:00 a.m., watched some TV, took an hour-long bath, and eventually went to work around ten. The office was an easy, breezy five-minute drive from my apartment. Sometime around seven or eight in the evening, I’d drive back home, play some games, eat some dinner, and fall asleep. That was my life, and I loved it. When Young Philippe arrived, that all changed. He was excitable and energetic, like a puppy, always looking for new things to do. I was not a doer. My number-one hobby in California was making plans on which I never intended to follow through. There was the time Young Philippe and I decided to join the San Francisco curling league and qualify for the 2010 Winter Olympics. And that other time when we planned to take all the cigarette packs and Red Bull cans from our Death Shrine and use them to build the body of a robot we had already named the Offense-o-Tron Deathousand. My personal favorite was when we were going to rent a pirate ship to sail us into international waters so we could set off illegal fireworks. These were some of our best adventures, and I never had to do any of them.

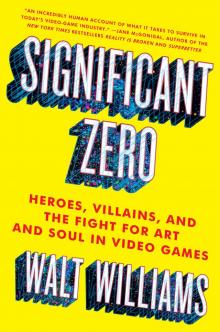

Significant Zero

Significant Zero